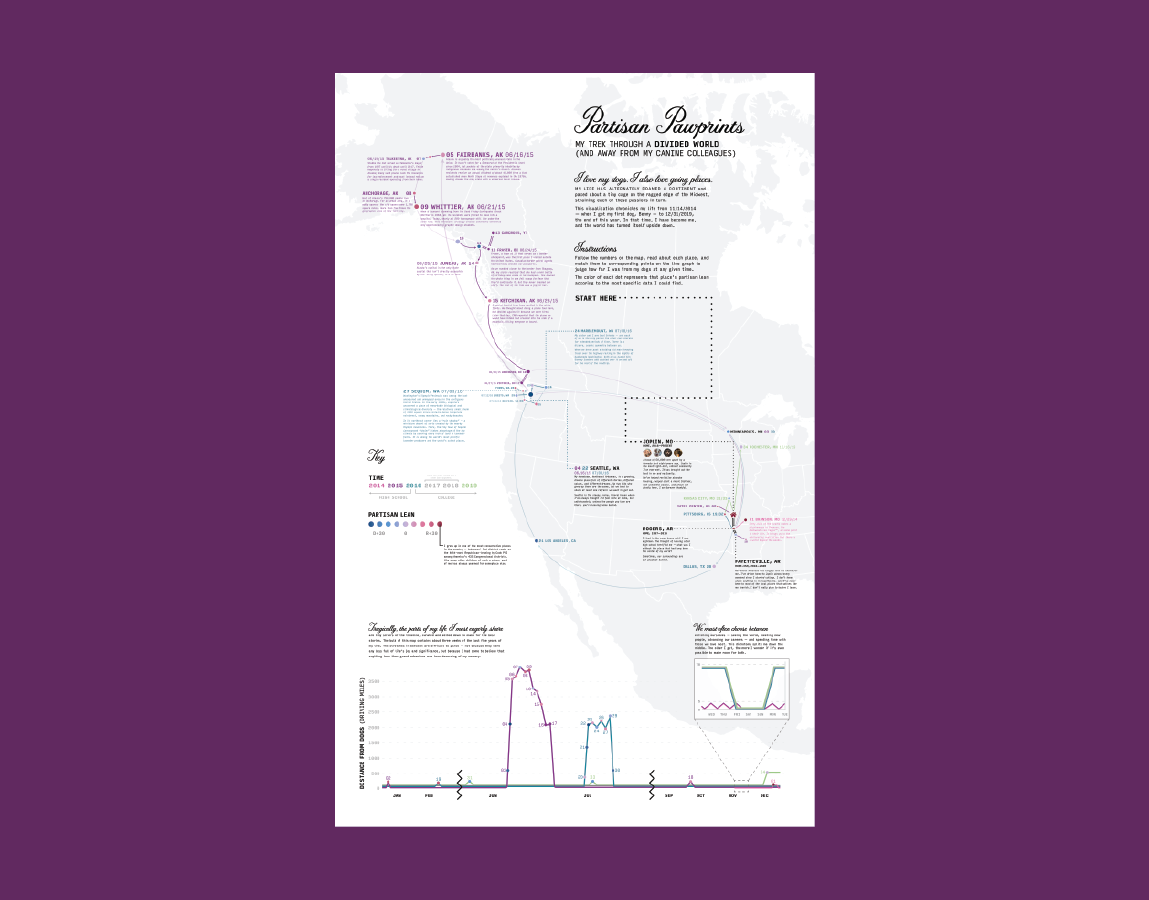

View the full, detailed research report in e-book form here.

INTRODUCTION

How might we empower neighborhoods to involve a larger and more representative share of their residents in decision-making and problem-solving processes?

One of the United States' most pervasive and destructive problems rarely receives the conversational limelight it deserves: we need 3.3 million units of housing more than we currently have. This drastic shortage has far-reaching consequences. Particularly in dense coastal cities, housing shortages create homelessness; it leaves many millions more of our poorest citizens without the money they need to cover food, transit, and healthcare.

Unlike many other wicked problems in our political discourse, however, there is no obvious federal solution to a problem so inherently local. The responsibility for these shortages falls on the thousands of zoning boards, planning commissions, and neighborhood-level organizations dotting the country that make ad-hoc decisions on housing developments in hours-long monthly meetings. Only a narrow slice of the population has the time, energy, and acumen to voice their concerns at these meetings, and that crowd tends to be older, wealthier, and especially resistant to change.

Inspired by an an episode of one of my favorite podcasts, Vox's The Weeds, I set out to level the playing field at these meetings and re-involve everybody in their neighborhood.

DISCIPLINES

Human-centered, UX

TOOLS

Adobe XD, InDesign, and Photoshop

Photos taken by me for various past projects.

LITERATURE REVIEW

You can view my full literature review here.

Neighborhood Defenders by Dr. Katherine Levine-Einstein

In Levine-Einstein’s analysis of neighborhood meetings, she found that neighborhood meetings disproportionately attract opponents to whatever development is on the table. They tend to defend their position on the basis of their neighborhood’s history or character, even if they’d stand to benefit from the development in the long run. This is because housing developments have rather immediate negative impacts on residents’ day-to-day lives (e.g. noise and traffic from construction) balanced against diffuse, hard-to-grasp benefits (e.g. increased property values, a higher standard of living).

A majority of residents would express indifference (functionally, soft support) to housing developments if asked directly*. However, their input is rarely taken into account at these meetings because they either don’t care or don’t know enough to attend. Furthermore, the general processes surrounding zoning and development are incredibly archaic, and few people have any knowledge surrounding them.

*The author cites an example where 57% of residents in a Boston suburb supported an affordable housing development, but 83% of those who showed up to planning meetings opposed it.

On a large scale, this phenomenon significantly tightens the housing supply, thereby raising the cost of existing housing as well.

PRIMARY RESEARCH

You can view a full summary of my primary research here.

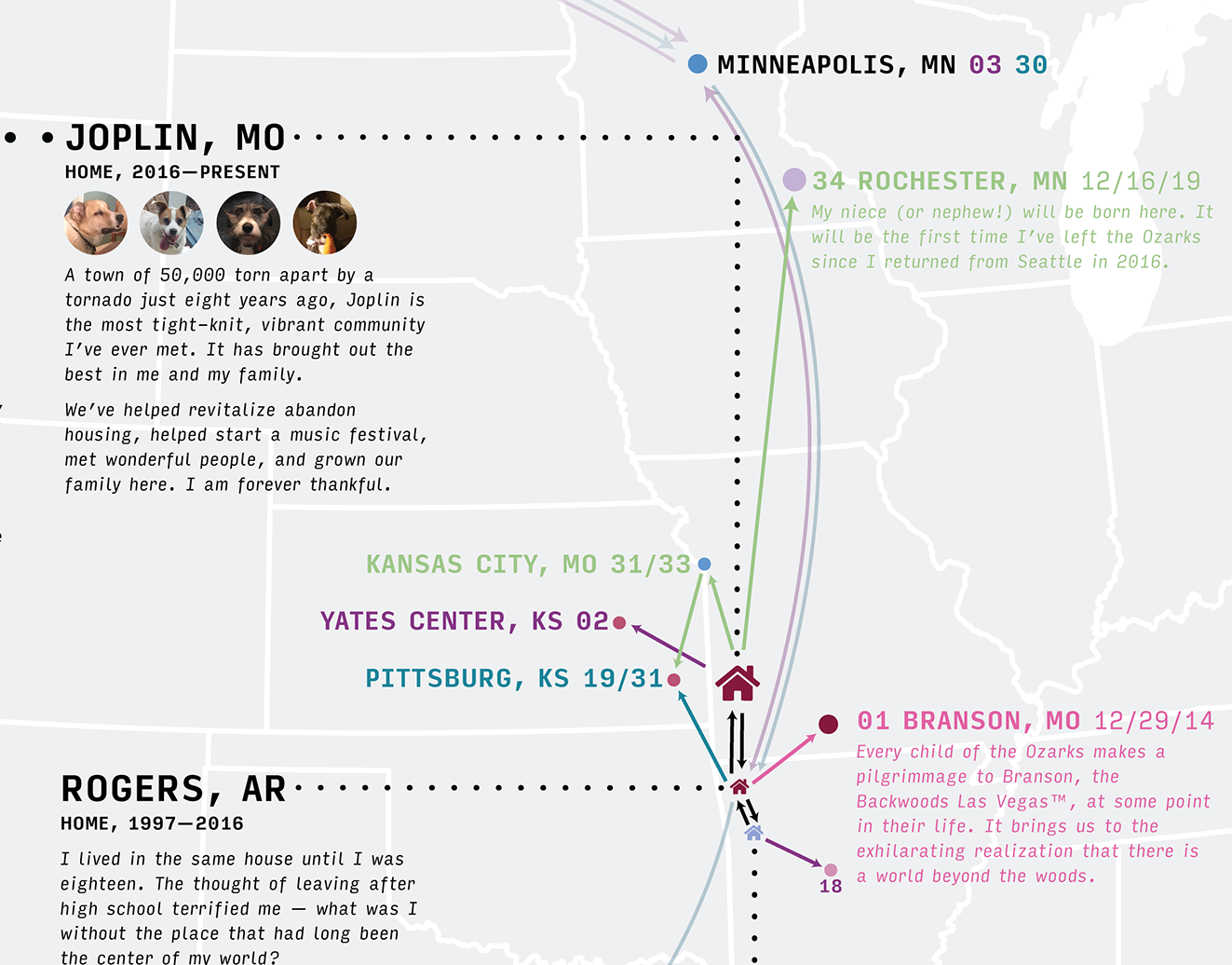

Design ethnography: My first step was, naturally, to attend a few neighborhood meetings for myself. Over the course of the semester, I went to three of my neighborhood’s monthly meetings. The North Heights Neighborhood Group is new and relatively young — it recently received 501(c)(3) designation and lacks a consistent source of funding. Engagement with North Heights meetings is expectedly low: in a neighborhood of about a thousand residents, attendance is typically 10 or fewer.

Democracy in this setting can be dysfunctional. At the second meeting, a small subset of the first meeting’s attendance (which was itself a tiny sliver of the neighborhood) made decisions for the full body. That’s a problem. Items on the agenda from the last meeting, stripped of their context and the people who advocated for them, received little credence and faded from the conversation. This is a long-standing trend. One month, attendance is high and ambitious plans are made, but the next month, fewer people can attend and any momentum on those initiatives is ground to a halt.

Survey: I surveyed 30 North Heights residents about a variety of issues, including their relationships with neighbors, involvement in the neighborhood group, and social media usage. I also asked them how they'd feel if a developer showed up to propose constructing a few different amenities on land near the neighborhood. Here's one example of the results:

LOW-INCOME APARTMENT BUILDING

13/29 respondents (45%) expressed clear support. Among those who went into the reasoning for their support, many cited a need for low-income housing.

04/29 respondents (14%) expressed soft support, indicating that they’d lean toward supporting the proposal, but that they’d like more information.

09/29 respondents (31%) expressed strong opposition, citing architectural design concerns, zoning, noise, traffic, and criminal activity.

Overall, this survey represents a pretty wide breadth of attitudes toward neighborhood involvement and development. Respondents were better-spoken on housing issues than I initially expected. We have plenty of NIMBYs who harbor resentment toward the poor or don’t want their life to be interfered with, but plenty of YIMBYs who indicate some level of awareness for housing issues.

DESIGN OUTCOME

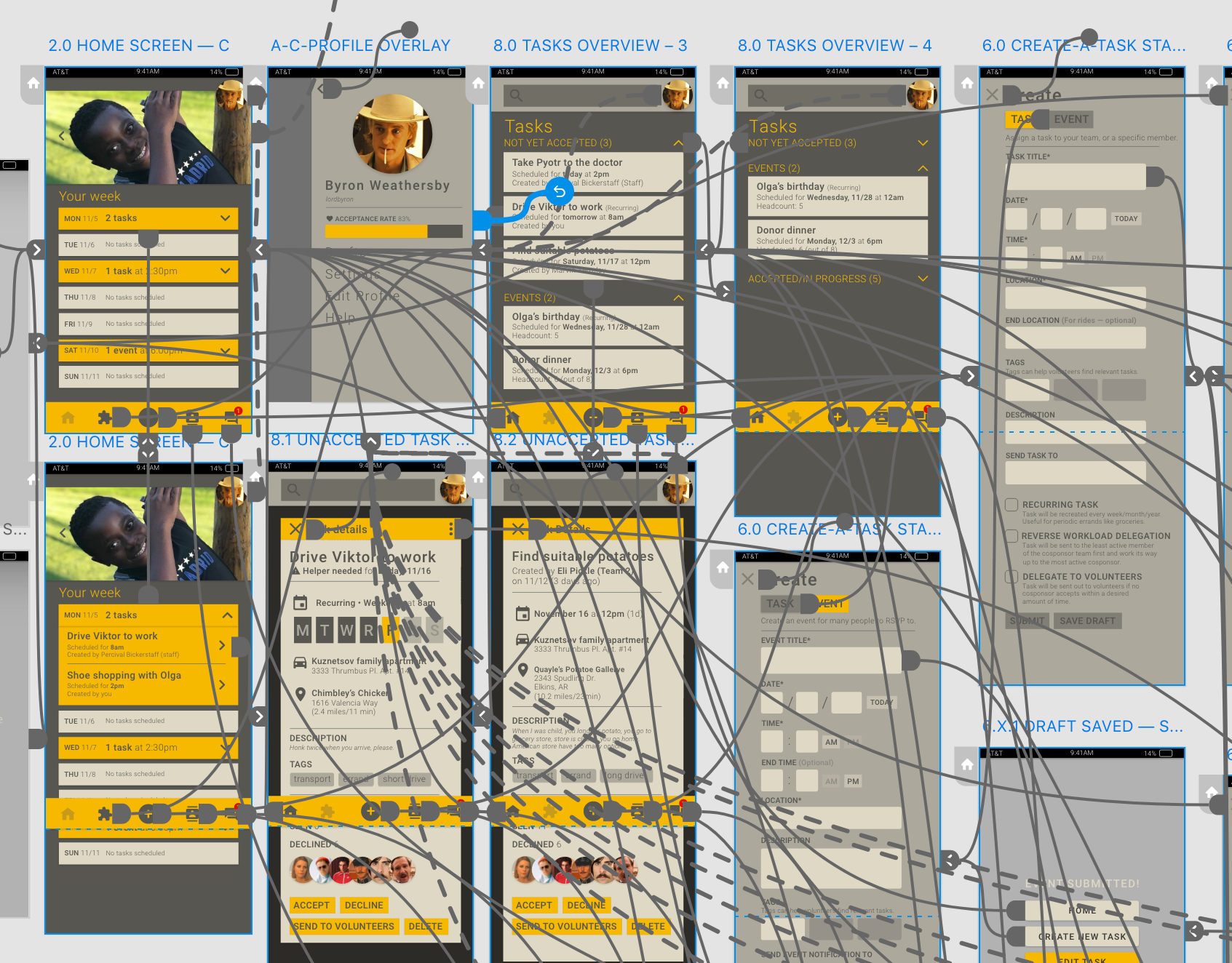

My design solution is a system called Community Blueprint. The program would be funded through HUD (or some other federal agency) with the goal of providing organizers the tools needed to reach and involve a broader share of their community in civic processes.

Images used only for academic purposes.

MEETING WITHOUT BARRIERS

The flagship element of Community Blueprint is a virtual meeting platform. Meetings would still take place in-person, but residents could attend virtually in the event that they can’t leave their home for whatever reason. This would also allow attendees to come for only the parts of the meeting they’re interested in, without having to sit through unrelated topics.

The platform would use speech-to-text and abridgment technologies — which are already used in many areas of information technology — to generate meeting minutes and transcripts. It could generate closed captioning to better include the hard-of-hearing, and simultaneously translate captions to other languages to serve non-native English speakers.

This running document exists in a collapsible tab on the side of the live video feed, helping participants keep track of the topic. In addition to keeping an agenda, meeting organizers could set a time limit for each topic, and a "shot clock" at the bottom of the interface would remind participants to stay on-topic and avoid rambling.

ON-TOPIC, ASYNCHRONOUS CONVERSATION

Each community would receive its own standardized website, where auto-generated meeting minutes and recordings migrate automatically. Residents can comment publicly on specific items in the minutes, allowing those with full schedules to participate asynchronously. Comments are character count-capped and could be auto-moderated for keywords, mitigating the tendency for online forums to devolve into senseless arguments.

REACHING THE UNREACHABLE

In a community where many folks lack access to smartphones — whether due to age, income, or tech savvy — any system intending to bolster the democratic process needs to reach those without constant internet connections. Voting and public comment through SMS messaging would allow those with lower-end mobile phones to participate asynchronously.

CONCLUSION

The final semester of my senior year was moved to online-only due to COVID-19 on March 12, 2020, as I was in the middle of this project. I still feel a little unsettled, as if I was prematurely ripped away both from my work and from the most wonderful and important people I’ve ever met. I viewed this project as having the potential to give back to my community, and though I’m content with how it turned out, I can’t help but wish I’d done more. Still, I'm one of the lucky ones.

As I drove home from what turned out to be my final in-person college class that day, I realized that Community Blueprint had gained an added layer of relevance. We don’t rely on our neighbors to a fraction of the extent to which we once did; it’s become common to live in a place for years and never meet the people who play out their lives across the street. Online forums like neighborhood Facebook pages become riddled with distrust, hate, and vitriol. Perhaps if we knew each other more, we'd love each other better.

The physical separation required by a global pandemic puts these tragic conditions under untenable strain. Now more than ever, we should know those who are physically close to us — those who might need our help in times of crisis, and who might need our help right now. We need to check in on each other whether it’s necessary or not, share our looming anxieties and the tiny joys that get us through the day. We are meant to be interdependent.